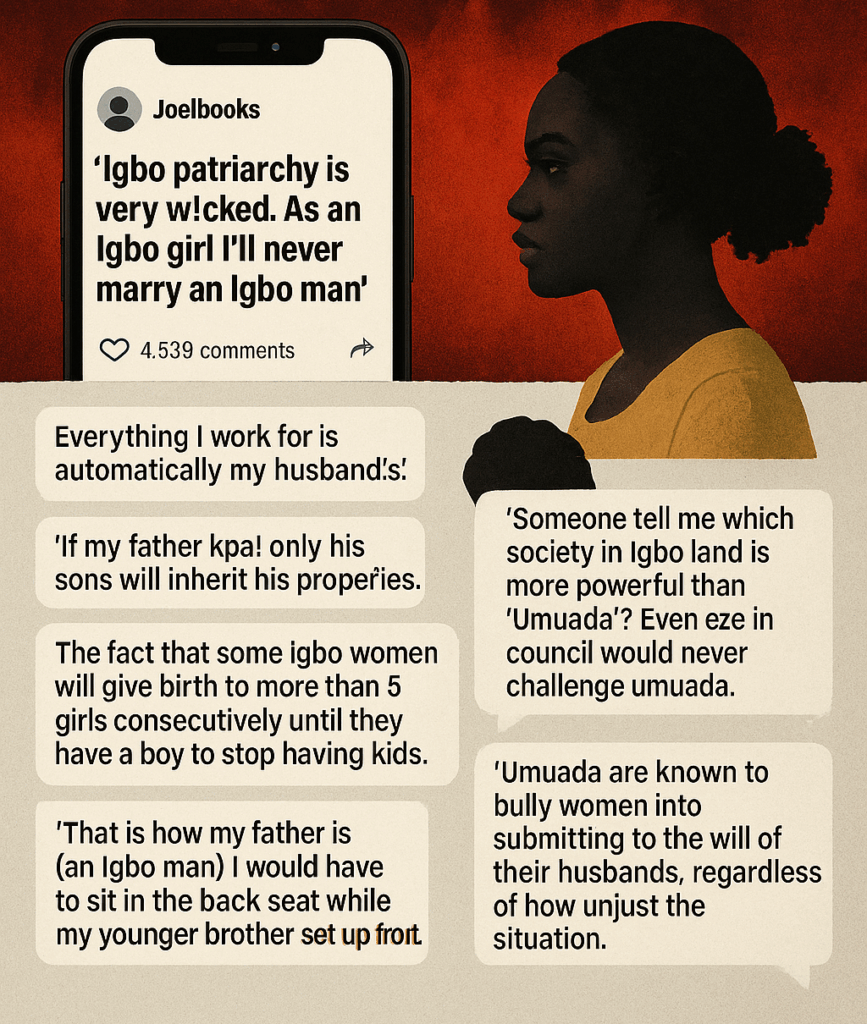

A social media storm ignited recently, spilling from the vibrant, often chaotic, forums of Nairaland onto the sleek interfaces of Instagram and X. The catalyst was a bold declaration from a young Igbo woman: “Igbo patriarchy is very w!cked. As an Igbo girl I’ll never marry an Igbo man.”

This single statement, a match thrown into a tinderbox of generational and cultural frustrations, exploded into a fiery debate that has forced a community to look in the mirror. The ensuing conversation, captured in hundreds of comments and quotes, is not just about one woman’s grievance; it’s a raw, unfilterered national therapy session, exposing the deep fissures in the foundation of one of Nigeria’s most influential ethnic groups.

A Litany of Pains

The original post, shared by a user named Joelbooks, laid out the charges with painful clarity. The anonymous woman argued that within the Igbo marital structure, “everything I work for is automatically my husband’s.” She lamented the intense pressure to bear a male heir, stating that a childless woman’s plight is “worse.” But the deepest cut, a wound that festers long before marriage is even considered, is the issue of inheritance. “If my father kpa! only his sons will inherit his properties.”

This sentiment found immediate and visceral resonance. In the comments, user ito_han_ shared a bewildering encounter: “I had an Igbo friend once, she found out I didn’t have a brother and immediately she said she feels sorry for my mom. I am from Edo state, I was really confused, why are you feeling sorry for my mom?”

The anecdote highlights a cultural chasm, where the absence of a male child is seen not as a family structure, but as a tragedy. User lov.amyy pointed to the physical and emotional toll of this preference: “The fact that some Igbo women will give birth to more than 5 girls consecutively until they have a boy to stop having kids. The toll that each pregnancy must have had on her 🥺”

The discrimination, many argue, starts in childhood. User s_daley_87 recounted a personal story of gendered hierarchy within the family unit: “That is how my father is (an Igbo man) I would have to sit in the back seat while my younger brother sat up front. I was never allowed to sit up front when my younger brother was present.” Another user, iluvbunny, lamented being sidelined in commercial settings in Abia state in favour of a male cousin, despite being the one with the financial means.

These testimonies paint a picture of a system where a woman’s value is intrinsically linked to the men in her life—first her father, then her husband, and ultimately, her son.

The Power of Umuada

The backlash to these accusations was swift and fierce, rooted in a defence of tradition and a different interpretation of Igbo cosmology.

A key counter-argument centred on the revered institution of the ‘Umuada’ – the daughters of a lineage. User mrvitalis passionately defended this, stating, “Someone tell me which society in Igbo land is more powerful than ‘Umuada’? Even eze in council would never challenge umuada.” He and others, like nnamdi640, argued that this proves the Igbo uniquely revere women, granting them a powerful, autonomous space to adjudicate on community matters, particularly burials and marital disputes.

“No tribe reverence woman like Igbos,” mrvitalis declared, challenging the very premise of the patriarchy charge. User noliogram offered a nuanced perspective, arguing that the criticised behaviours are not universal Igbo practices but individual misinterpretations. “In my own part of Igbo Land, Men willfully give their seats to Women… We believe Women need their waist intact to carry children, and all care is taken to save Women’s waist.”

Other defenders, like freeborn004, shifted the focus to the successes of Igbo women, attributing their famed resilience and educational drive to the same cultural structure. “Imagine talking about Igbo men that even women from other tribes including Yoruba are wishing to marry because they are known to look after their women.”

There was also a strain of dismissal, with comments like agadez007’s “All these online igbo feminists… will later marry the same Igbo men quietly,” and Tochi3’s blunt “..very useless, senseless Laptop..” These reactions frame the critique as an inauthentic, foreign-influenced rebellion against a natural and functional order.

Empowerment or Enforcement?

However, the defence of the ‘Umuada’ was itself fiercely contested, opening a second front in the war of words. User Kobojunkie fired back at the romanticised view of the institution, calling it a “gang of women who are known to bully women into submitting to the will of their husbands, regardless of how unjust the situation.”

This reframing turns the ‘Umuada’ from a symbol of female power into an instrument of patriarchal control—a group that polices women to ensure compliance with traditions that ultimately serve male interests. “I saw a documentary sometime ago of how that group has been used in many cases to silence justice, all in the name of supposedly keeping peace and tradition,” Kobojunkie added.

User Dtruthspeaker echoed this, calling it “a case of an oppressor praising his henchman” and describing the ‘Umuada’ rituals as being treated “like a gathering of children.” This critique suggests that the autonomy granted to the ‘Umuada’ is a curated one, limited to enforcing a system they did not design.

A National Conversation

What makes this debate uniquely Nigerian is how it quickly transcended Igbo borders. User astoldbychels attempted to broaden the scope, stating, “The patriarchy is alive and well in Nigeria, and it doesn’t discriminate by tribe. Nigerian men and misogyny are like 5 and 6.” Yet, the intensity of the Igbo-specific debate suggests a particular configuration of patriarchy that many find especially potent.

For every critic from outside the tribe, there was a defender ready to counter-attack. When Morenikeji090 from the South-West criticised the practice, he was met with retorts about the disrespect shown to Yoruba Obas. This tribal crossfire, while often deflective, underscores that this is a national conversation happening through a specific, intensely debated lens.

Amidst the anger and defence, threads of hope and change emerged. User sing_kamso declared, “This mindset will die in my generation…. My sons will grow up to not only respect themselves but respect women in all shapes and sizes as well in Jesus name amen.” This sentiment, echoed by others, points to a new generation determined to curate the best of their culture while discarding its toxic elements.

Crucially, user Yankee101 pointed to the power of modern law: “The Supreme Court had to step in to break that tradition. Women can now inherit. Go to court if they try to deny you your rights.” This highlights the growing tension between unaltered tradition and the enforceable rights of a modern nation-state.

Heritage in the Balance

The online firestorm over Igbo patriarchy is more than just social media noise; it is the sound of a culture in a painful, necessary, and public evolution. It is the sound of daughters demanding their birthright, wives seeking partnership over subjugation, and sons and husbands being called to account.

It is a conversation filled with pain, pride, deflection, and hope. The defenders rightly point to institutions like the ‘Umuada’ as evidence of a complex culture that is not simply oppressive. The critics, with their raw, personal testimonies, rightly demand that this complexity should not be an excuse for injustice.

As the debate rages from the comment sections of Nairaland to the DMs of Instagram, one thing is clear: the future of Igbo culture will not be decided solely in the village squares by the elders, but also in the digital town halls by a new generation. A generation that, while fiercely proud of its Naija heritage, is asking the hard questions about what it truly means to be #NaijaStrong when half of its people feel their strength is being suppressed.