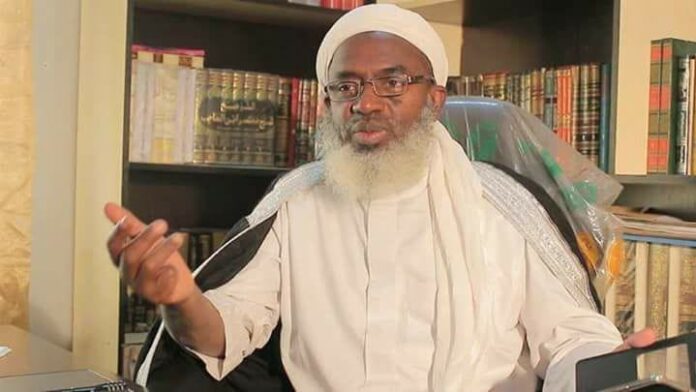

Islamic scholar Sheikh Ahmad Gumi has accused the United States of a cover-up in the debate over an alleged Christian genocide in Nigeria, deepening a national argument that has sparked strong reactions from leaders and citizens.

The controversy began after a New York Times report suggested that U.S. airstrikes in Nigeria were based on unverified information from a man identified as Emeka Umeagbalasi, a small-scale trader in Onitsha, Anambra State. The article said Emeka, described as the operator of a tiny NGO, claimed he had documented “125,000 Christian deaths” using internet searches — a figure that many experts and Nigerian officials say is unsubstantiated and not rooted in verified data.

The story stirred up a strong response across the country, and criticism reached a new level when former Kaduna Central Senator Shehu Sani took to social media to condemn how the report was used. Sani called it “unfortunate and tragic” that unverified claims from a market trader could influence U.S. lawmakers and even lead to military action. In a post on X (formerly Twitter), he said the situation was “one of the most foolish and comical historical events in our lifetime,” and he described the report as shameful.

But Gumi, known for his controversial views on security and interfaith issues in Nigeria, has gone further. In a post on Facebook, he said U.S. intelligence “is not stupid,” adding that American authorities knew what they were doing but wanted a Nigerian story as a cover for their own interests. Gumi’s claim suggests that the U.S. used the narrative of Christian suffering to justify political or military involvement, though he did not provide evidence to support this view.

At the centre of the issue is a report that the United States, under former President Donald Trump, launched military airstrikes in Sokoto State after citing concerns over killings of Christians. While the U.S. has stated that it took action against violent extremist groups responsible for terror attacks, critics argue that the justification given in global media has been exaggerated or inaccurate.

The debate over whether Christian genocide is happening in Nigeria is not new. Analysts say Nigeria’s complex conflict — involving Boko Haram, ISWAP, bandits, and ethnic militias — affects both Christian and Muslim communities, with civilians of all faiths suffering. Security data shows that violent attacks kill and displace many Nigerians each year, but experts caution against using broad terms like genocide without solid evidence.

Many religious and civil society groups in Nigeria have strongly rejected the genocide label. The Ulamau Wing of the Conference of Islamic Organisations said claims of Christian genocide are a “false narrative” and warned against foreign military intervention that could worsen Nigeria’s fragile peace. The group said security challenges in the country affect all Nigerians — Muslims and Christians alike — and should not be used as a reason for external interference.

Meanwhile, political voices have also weighed in. Shehu Sani, in his social media post, criticised the reliance on flawed sources and questioned how unverified data could influence serious decisions. He called on Nigerians to reject foreign intervention and stressed the importance of national dignity and sovereignty.

The situation has also created tension between Nigerians who feel the narrative of genocide is being used to distract from real security failures, and those who believe more must be done to protect vulnerable communities. Some civil rights groups argue that the Nigerian government must do more to secure all citizens and address ongoing violence that has lasted for more than a decade.

Gumi’s response has itself drawn criticism from some Nigerian organisations. The Campaign for Democracy warned that comments like his could harm national unity and worsen diplomatic ties with the United States. The group described such rhetoric as “irresponsible, divisive, and capable of inciting violence or extremism,” urging Nigerian leaders to caution against statements that could create deeper religious divides.

The United States’ role in Nigeria’s security challenges has been a matter of debate for years. While American officials say they support Nigeria’s fight against terrorism, some Nigerians view foreign involvement with suspicion, fearing it may lead to loss of sovereignty or be driven by political motives. Others see international assistance as valuable support to help Nigerian forces tackle well-armed extremist groups that have proven difficult to defeat alone.

In the midst of all this, Nigerians on social media and in public discussions continue to disagree over the scale and nature of the violence. Some insist the term genocide is appropriate based on the number of attacks on Christian communities, while others argue that the term is being misused and oversimplifies a complicated conflict that kills people regardless of religion.

Religious leaders have urged calm. Many faith organisations emphasize that violence in Nigeria is a national emergency affecting all believers and that the solution must focus on peacebuilding, justice, and improved security, rather than inflaming tensions or pointing fingers at foreign governments.

For now, the argument between Sheikh Gumi and Shehu Sani reflects broader disagreements over how Nigeria’s problems are portrayed at home and abroad. Both men are vocal figures whose statements attract attention, but their different interpretations show how sensitive and contested the narrative around Christian genocide has become.